Lifelong dreams and fantasies sometimes have a way of turning into reality – a reality that surpasses the imagination itself!

Several years ago, just on the verge of beginning a promising new job and moving into an apartment of my own, I decided to celebrate my bright prospects by spending a few days in Paris, a city dear to my heart. Among the many attractions I planned to visit, one destination in particular beckoned enticingly – the Paris Opera House, also known as the Palais Garnier. I was determined to gain access to the legendary backstage of the theater, and the fact that I had worked as a stagehand at the Metropolitan Opera gave me reason to feel optimistic. My pilgrimage to this theater was inspired not only by technical curiosity, however, but by an ardent desire to revisit the site of treasured memories. At the impressionable age of twelve, my life changed forever when I was taken to my first two operas (Rigoletto and Tannhäuser) by a devoted aunt and uncle who lived in Paris and hosted me for an entire summer. Over the years, I had never ceased yearning to relive those two magical nights. What’s more, ever since childhood, I had been obsessed by the tale of the sinister Phantom who held the Palais Garnier in the grip of his evil genius. As I approached the building, resplendent even on a drizzly autumn afternoon, never could I have foreseen the experience that was about to unfold.

I made my way towards the courtyard in the back of the theater, where the stage door is located. I had formulated a plan of approaching a stagehand (in my passable French), introducing myself as a colleague from the Met, and stating my keen interest in visiting the theater. Back in New York this idea seemed perfectly feasible; now that I was actually here, I wondered what kind of reception I would get. Parts of the theater – the magnificent staircase, lobbies, auditorium – are open to the casual tourist for a nominal fee; the stage, however, is most assuredly off-limits.

Almost immediately I had begun to notice men entering and exiting the stage door who were dressed in blue, uniform-like work jackets. I assumed that these were machinistes, as they are called in French. Before long, two young guys appeared, crossed the courtyard and emerged onto the sidewalk where I was standing. This was my chance, now or never . . . I stepped up to the two fellows and – quel bonheur!! - was elated to see that they were cautiously intrigued by my appeal. “We could say he’s a cousin from the United States in case anybody asks,” one proposed to the other. But from what I could gather, they were on afternoon break, and I found myself once again standing alone at the courtyard entrance, wondering whether they would really return as they had assured me. After a brief wait, however, I spotted them across the street, headed back in my direction.

The stagehands’ concern in creating a fictitious kinship for me had been unnecessary: a casual “Salut” got us past the gentleman who presided over the stage entrance desk, with whom they were obviously well acquainted. I was in!! Arriving at the end of a corridor, one of the stagehands politely took his leave, entrusting me to his younger comrade, who had thus far hardly spoken. In a somewhat shy manner that revealed a desire to accommodate, he led me through a doorway and indicated, “Voilà, le plateau” – the stage!

How many hours had I spent, scrutinizing a souvenir photograph of that stage, to now find myself strolling across its vast wooden expanse, at this hour completely deserted. The stage in the Palais Garnier is, actually, bigger than the main stage of the Met, although of course it does not contain the additional spaces comprising the left, right and rear wagons that are such a technical highlight of the Met. Leading me towards the upstage wall, my guide pulled aside a heavy curtain which covered the entrance to what I immediately recognized as the famous Foyer de la Danse, the domain of the Paris Opera Ballet dancers. This opulently decorated ballet studio is, in reality, an extension of the stage itself. I tried to assimilate all the information my guide imparted, obviously pleased at my great interest in his theater.

An elevator with the familiar “Otis” name took us underneath the stage, where rows of capstan-like wooden wheels evoked the original stage machinery of 1875. An eerie feeling passed over me as I grasped the worn handles. In fact, from the moment I had stepped into the backstage area, it was impossible to remain unaware of the haunting atmosphere that permeates this part of the building. I have often wondered why it is that old theaters – more so than other types of buildings – seem to retain in the very air an essence of the past, as if the memories of long-ago days still vibrate within their walls . . . It had definitely been so in the old Metropolitan Opera House, which opened only eight years after the Palais Garnier.

Continuing our descent into the sub-levels, we arrived at a grating in the floor that afforded me the bewildering sight of a pale, ghostly fish swimming through murky water. I realized in a flash that the water visible through the grating must be part of the legendary subterranean lake over which the massive foundations of the building had been constructed. “The Phantom’s Lake!” I blurted out, barely able to contain my excitement at this discovery, much to the amusement of my guide, who confirmed, “Oui, le lac du Fantôme,” and explained to me that the fish are fed and tended by the firefighters who safeguard the theater.

Back on stage, we now proceeded in the opposite direction – ascending the fly galleries level by level, finally reaching the dizzying height of the grid. Following my guide through a small aperture in the wall, I was greeted by a view that left me bedazzled: we had stepped through the pediment of the fly tower onto the green copper dome that crowns the opera house. Suddenly, Paris sprawled gloriously around us with its many familiar landmarks, the grayish afternoon having given way to an autumnal, sunlit sky. Hovering above us – startlingly close – was the huge bronze Apollo raising his lyre to the heavens. If ever there were a moment I knew would remain permanently imprinted in my mind, this was it.

When we returned to earth, my young guide – to whom by now I felt greatly indebted – concluded this spectacular tour by taking me into the orchestra pit, the sumptuous gold and red auditorium with its massive chandelier, and out into the area of the Grand Staircase. A superb guide, to say the least, who now proposed a moment of relaxation at an elegant cocktail lounge just across the street.

After a couple of Jack Daniels, during which we discovered many interests in common including a love for the sea, my guide – whose name was Thierry – inquired as to my plans for the evening. Alas, at the moment I had none. Current performances at the Opéra, including this evening’s Macbeth, were sold out. “Why not come with me when I go to work tonight and watch from the wings?” “On the stage?!” “Of course! But first, would you like to join me for dinner?” This was more than I could have ever hoped for!

As we entered the employees’ canteen at the Opera House I thrilled at the prospect that lay ahead. My host glanced mockingly at the bottle of Coca-Cola on my tray (as opposed to the small bottle of wine on his), but when I reached for my wallet to pay for my steak dinner, the smiling mademoiselle at the register waved me on . . . it was already paid for. We ate quickly; the afternoon had sped by and curtain time was rapidly approaching.

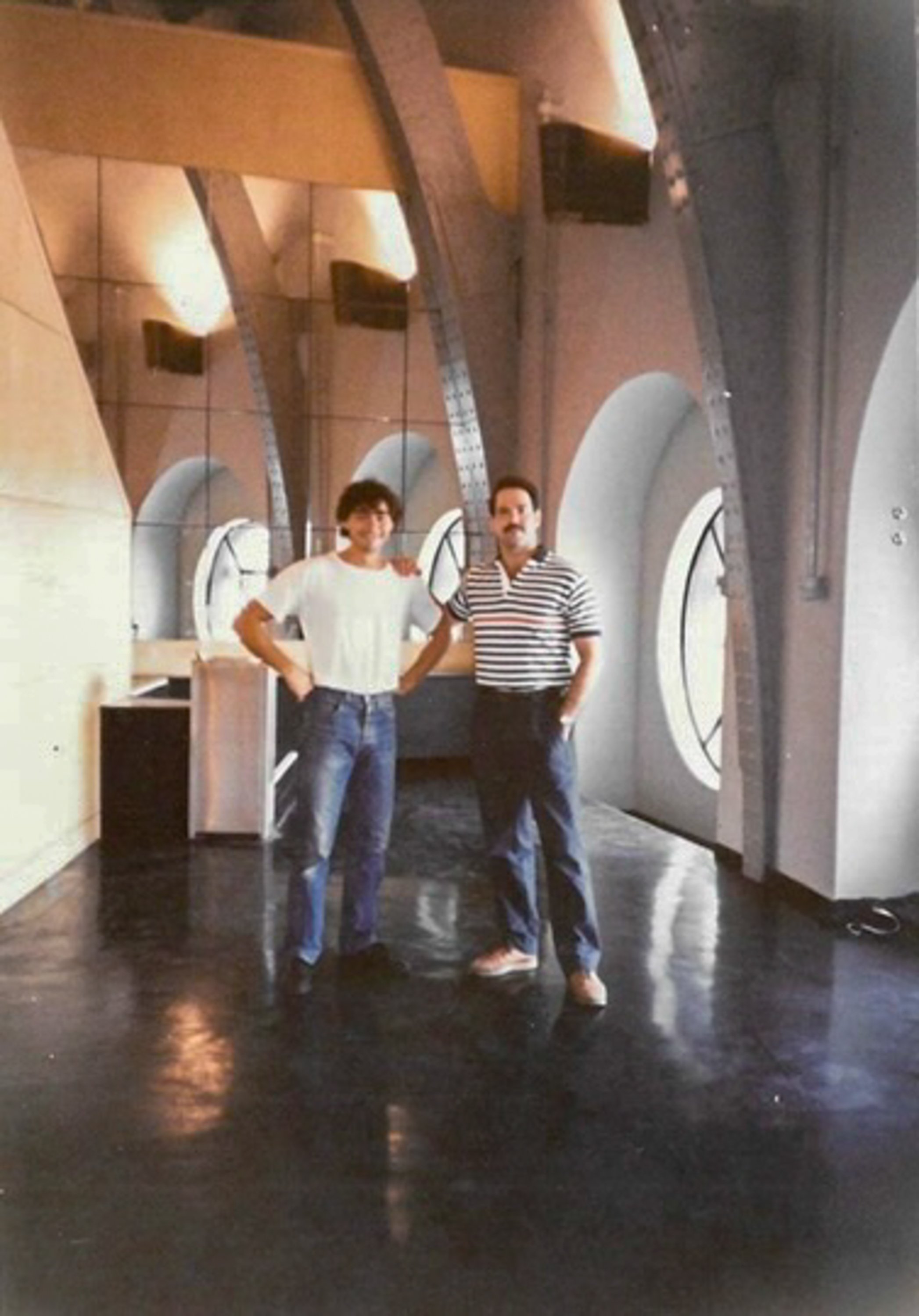

Watching a performance from the wings of a stage was not a new experience for me, but as I followed the exploits of Macbeth and Lady (Renato Bruson and Shirley Verrett), I marveled at the unbelievable stroke of luck that had brought me as a backstage guest to the very theater where I had had my first encounter with opera, the theater that had vividly dominated my imagination for so many years. I felt pride at being introduced as a “machiniste de New York” to several of Thierry’s comrades, who inquired with great interest concerning the mechanics of the Met stage. Furthermore, I was impressed by the relaxed efficiency that was evident backstage. My presence never aroused more than a passing glance, even when Thierry brought me – with the chorus already assembled – to the front of the stage so that a fellow stagehand might take a snapshot of us as a souvenir of the evening.

We watched the last act from a light bridge above the proscenium. I could see that Thierry was as enthralled by the music and the performance as I was, and as Macbeth died and the chorus intoned the triumphant finale, he turned to me and exclaimed, with sincerity and justifiable pride, “Bob, I am very happy that you are here tonight!”

Left by myself for a time while the stage was being cleared, I waited in the empty dressing room corridor, lost in a happy reverie, and wondering about the plans my friend had mentioned for later. The night’s labors finally over, Thierry brought me into the stagehands’ locker room where a cabinet that stood behind a small counter was being unlocked. Inside the cabinet was a surprising array of bottles containing alcoholic beverages. “La tradition,” indicated my host, as I joined the stagehands in a convivial nightcap. I said my “bon soirs” to the fellows I had met, and we made our way to the stage door exit.

Outside in the courtyard a tall, attractive young lady affectionately greeted my companion, who in turn introduced her as his girlfriend, Anya. Graciously insisting that I take the front seat, she climbed into the back of Thierry’s compact French automobile, and without further ado we were off for a post-performance snack. What better way to end a glorious afternoon and evening than to be taken to a private club for some genuine French onion soup and a bottle of wine? Truly, the events of this day had exceeded my wildest hopes!

A few days later I was again in the vicinity of the Opera House, and on impulse decided to see if my friend was there. The stage door guard escorted me to the stagehands’ locker room, where I was told he’d left already but would be in in the morning. I wondered if they would mention to him that I had been there. The next evening, while resting in my hotel room, the phone rang. My friend had not only heard of my visit, he was in the hotel lobby waiting to take me to dinner! I was totally elated; being on one’s own in a foreign city – even Paris – can get a little lonely after a while. This time, Thierry and his charming girlfriend were joined by another member of the Paris Opera – a witty young fellow named Claude who worked in the scenic design department.

Perhaps it was the allure of an autumn evening in Paris, or the poignant Russian songs accompanied by cimbalom, or the deliciously insidious green drinks that bore the name of the club they took me to – The Slavic Soul - but somehow I had never felt such happiness and camaraderie in the midst of persons whom I barely knew. And if, at two in the morning, we wound up staggering slightly on the quiet sidewalk, our toasts that night had been drunk by turns to France and the U.S., to Paris and New York, and to l’Opéra and the Met!

When my last day in Paris dawned, I planned to telephone my friend to bid him farewell and to thank him for having made this vacation so memorable. Shortly before dinner my phone rang, and to my delight it was Thierry himself, who could not let me leave his city without a final get-together. When we entered his car, he produced a surprise gift which touched and astonished me. There in the back seat was a magnificently sculpted Greek head, larger than life, with beard and laurels, mounted in a medallion of about twenty-one inches in diameter. Even though the sculpture gave the appearance of solid marble, it was constructed of some kind of molded plastic, very light in weight. This remarkable object was nothing less than part of the scenic decor that had been used in a Paris Opera production (Iphigénie), and was something that Thierry had obviously treasured. I realized the significance of this gesture, and could hardly find the words to express my gratitude at this generous token of friendship.

At some point during dinner, the subject of the Opera House naturally came up. Thierry began talking about the use of horses in the past, and the fact that there were stables in one of the sub-levels. This in itself was no surprise to me, an avid reader of Gaston Leroux’s novel. But I was completely taken aback when Thierry matter-of-factly suggested we go see the stables immediately after dinner! Amazed at his constant willingness to share his knowledge of the vast theater, I jumped at a final opportunity to explore mysterious regions unknown to the public at large.

There was no performance at the Opéra that night, and we parked in the empty courtyard in the back. The solitary guard knew Thierry, and never questioned the excuse that he needed to retrieve something from his locker at that hour.

Set pieces from the ballet Romeo and Juliet were clustered on the dormant stage. Apart from the sound of our voices, a great stillness reigned all about us. When we descended into the cellars, I at first recognized the surroundings from our previous tour, but now we headed in a hitherto unexplored direction. Perhaps it was the awareness that above us the theater was dark and empty, but the lugubrious aura of this subterranean region was palpable. Every few feet one encountered narrow doorways covered with bars, passageways disappearing into blackness, steps leading up to cell-like chambers . . .

The situation grew more unnerving when we reached the area in which the stables were located. It was obvious from the total absence of illumination that they had not been used for many years. The flame from a plastic cigarette lighter Thierry produced cast a faint glow on the stalls. No Hollywood set could convey the melancholy and foreboding nature of this place. I had to admire my friend’s thorough familiarity with these unfrequented areas of the building, but the fact that a little disposable lighter was the only thing between ourselves and total darkness was slightly unsettling. Coming to a dead end, we made our way out of this forsaken corner of the Opera House and headed back up to stage level. As we were leaving, Thierry turned to me and confided, “Bob, we are two very lucky guys!” I heartily agreed; but that phrase would come back to haunt me more than once. I wondered later, had he known something about the nether regions we had just visited that I hadn’t . . . ?

“Okay, Bob?” Thierry asked with a jubilant grin when we emerged onto the safety and familiarity of the sidewalk, “L’Opéra de Paris!” As we gazed at the illuminated façade, looming against the night sky, I felt a sense of wonder at the miraculous turn of events that had taken me from one end to the other, throughout the height and breadth of this majestic theater – even into its dark and secret recesses. In my heart I bid an affectionate farewell to the Palais Garnier, convinced that, in some inexplicable way, the Opera House had welcomed back the twelve-year-old boy who first experienced the joys of Verdi and Wagner within its hallowed walls.

Years have passed, and still I occasionally find myself contemplating the great Greek head (affectionately nicknamed François) which hangs in my living room, reminding me with its penetrating stare of that whole wondrous experience. I know that Thierry became one of the first stagehands to work in the new Opéra Bastille, and eventually moved to a seaside town in Normandy, where he was named Meilleur Ouvrier de France in recognition of his skill as an upholsterer and furniture designer. Wherever he is, I will always remember him with gratitude - my genial guide to the magnificent domain of the Phantom, the Paris Opera House!